Gallery

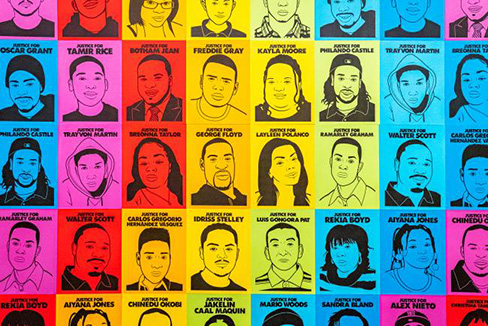

Oree Originol, Justice for Our Lives, 2014-present, 78 digital images, 18x24in.

Inspired by the Black Lives Matter movement, Justice for Our Lives is an ongoing online and public social justice artwork. Using original photographs, Originol creates black-and-white digital portraits of men, women, and children killed during altercations with law enforcement. The artist makes each portrait available for download for community members to use. He also creates dynamic, large-scale installations, like the one seen here, placing them in public spaces to draw the attention of passersby.

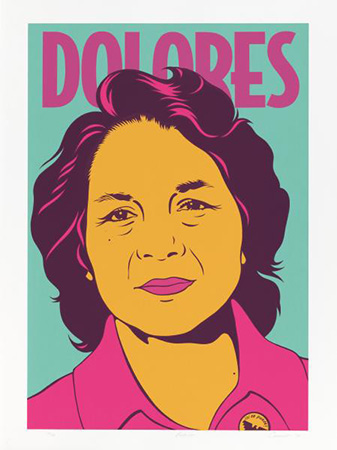

Barbara Carrasco, Dolores, 1999, screenprint on paper, 26x18in.

Carrasco chose to create a portrait of Dolores Huerta at a time when the groundbreaking labor organizer was sadly underrecognized for her pivotal role as the cofounder of the United Farm Workers union. The brightly hued print, which references Huerta by first name only, urges viewers to recognize female leadership. The close-up of Huerta’s face recalls Andy Warhol’s celebrity portraits, casting a beautiful and tireless labor leader as a new kind of icon.

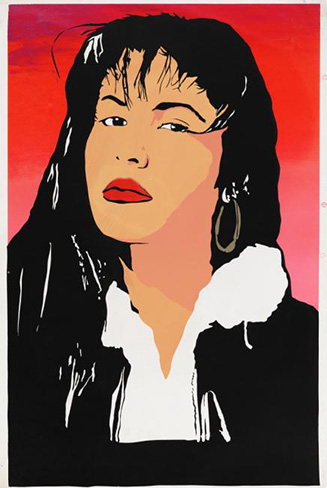

Rodolfo O. Cuellar, Selena, A Fallen Angel, 1995,

screenprint on paper, 33 1/8 x 21 1/2in.

Cuellar’s large-scale print depicts singer Selena Quintanilla in 1995, the same year of her tragic murder. The intense public outpouring of grief upon her death revealed the extent to which the bicultural Latina singer had become a role model to a generation of young people across the United States and Latin America. To convey her iconic status, Cuellar monumentalized the cover image of her best-selling album, Amor Prohibido (Forbidden Love; 1994).

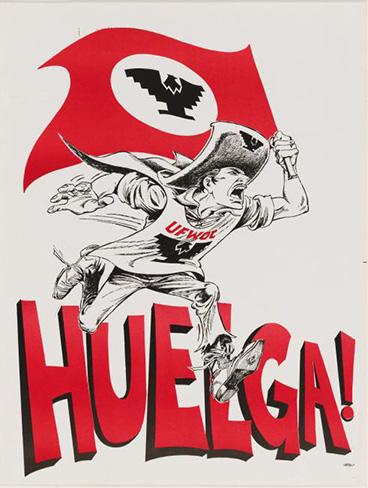

Andrew Zemeña, Huelga!, 1966, offset lithograph on paper, 24x18 1/2in.

Zermeño created Huelga! (meaning “strike” in Spanish) as his first poster for the United Farm Workers. Don Sotaco, the recurring figure in Zermeño’s posters and political cartoons, is a representative striker whose honorific title “Don” (esteemed; sir) conveys respect. Dressed in tattered pants and with a hole in his shoe, Don Sotaco rushes forward with a sense of agency as well as urgency. “I was trying to show the spirit of the workers . . . who were attacking the status quo,” Zermeño recalled. Brandishing a UFW flag proclaiming the strike, Don Sotaco—and by extension the union—calls for action from farmworkers and their supporters.

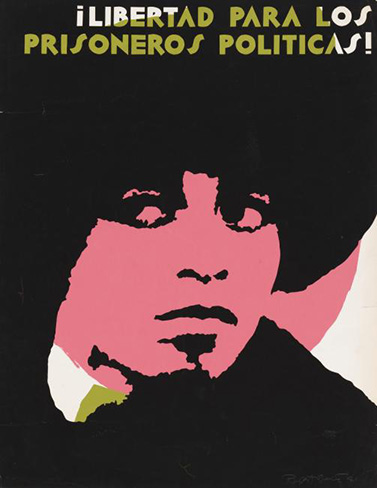

Rupert García, ¡LIBERTAD PARA LOS PRISIONEROS POLITICOS!, 1972, screenprint on paper, 24 3/8 x 18 3/4in.

García created several posters demanding the release of scholar and activist Angela Davis after she was famously jailed and prosecuted for several crimes, including conspiracy to commit murder. In what would become his signature approach to portraiture, García zooms in on the subject’s face and applies color in an abstract way. He prominently portrays Davis’s iconic Afro, which made her into a recognizable symbol of the Black Power movement. To convey Chicanos’ solidarity with Davis and her advocacy for prison reform, García added “Liberty to all political prisoners!” in Spanish. His language choice made his message accessible to Spanish-speaking people.

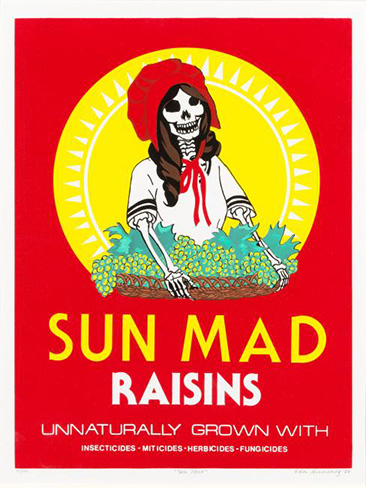

Ester Hernandez, Sun Mad, 1982, screenprint on paper, 20x15in.

In Sun Mad, Hernandez reconfigures the cheerful branding of the Sun-Maid raisin company into a grim warning. In response to her family’s exposure to polluted water and pesticides in California’s San Joaquin Valley, Hernandez sought to unmask the “wholesome figures of agribusiness,” such as the Sun Maid. The skeletal figure draws attention to the dangers and adverse effects of the various chemicals listed in the print’s lower register.

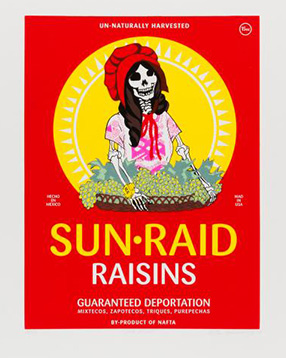

Ester Hernandez, Sun Raid, 2008, screenprint on paper, 19 3/4 x 15in.

Twenty-six years after her original, Hernandez reimagines her classic Sun Mad poster as a condemnation of U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement. In addition to changing the title from Sun Mad to Sun Raid, she outfits the calavera (skeleton) with an ICE wrist monitor and a huipil, a traditional indigenous garment. This latter reference suggests how indigenous people from Mexico and Central America represent a segment of undocumented immigrants in the U.S. Hernandez issued this print at a time when the George W. Bush administration was being widely criticized for its high level of workplace raids.

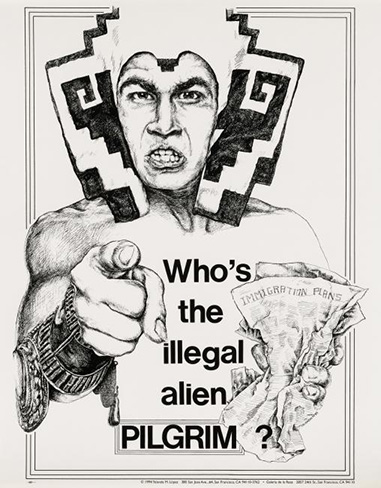

Yolanda Lopez, Who's the Illegal Alien, Pilgrim?, 1981, offset lithograph on paper, 22 1/2 x 17 3/4in.

López conceived an early version of her iconic poster Who’s the Illegal Alien, Pilgrim? while working on a local campaign in response to President Jimmy Carter’s Immigration Plan. The Aztec warrior’s stance recalls that of Uncle Sam in James Montgomery Flagg’s “I Want You” army recruitment posters, pointing a finger at the viewer and ordering young men to enlist. In mimicking Flagg’s iconic image, López gives her poster a subversive authority. Her question directed at “pilgrims” interrogates who can identify others as “illegal aliens,” especially since Mayflower settlers from Europe arrived in the Americas without “papers.”

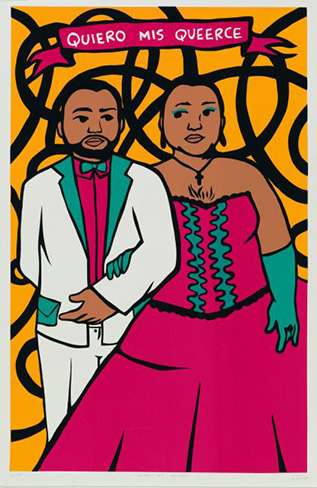

Julio Salgado, Quiero mis Queerce, 2014, screenprint on paper, 38 3/4 x 18 1/2in.

Inspired by Frida Kahlo’s well-known painting Las Dos Fridas (1939), Salgado employs a similar duality to reflect on his challenges as a gay teen hiding his femininity. As a young man, Salgado wanted a fifteenth-birthday celebration, or quinceañera, a traditional coming-out ceremony reserved for young women. When the artist turned thirty, he created this image, he said, to “honor the little boy who didn’t get a quinceañera.”

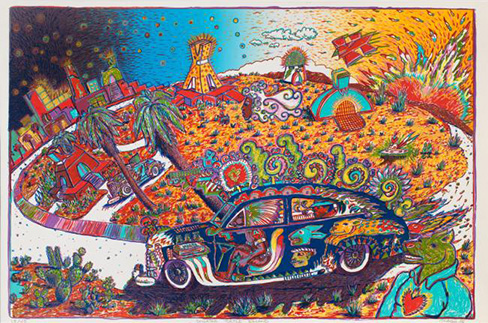

Gilbert "Magu" Luján, Crusing Turtle Island, 1986, screenprint on paper, 24 1/4 x 36 1/2in.

Magu’s fantastical landscapes imagine a world where Chicano culture is dominant. Cruising Turtle Island—which references a Native name for North America—pictures indigenous figures riding Chicano lowriders and “speaking” through ancient Mesoamerican speech scrolls. The anthropomorphic dog seen at the lower right is a common figure in Magu’s art that he employed, in his words, as “a metaphor for indigenous Mexican-Indian heritage.”

Descriptions from Smithsonian American Art Museum