Artists

Discover some of the most influential disco artists of the 70s such as Donna Summer.

Songs

Listen to some of the best disco hit songs of the 70s like Gloria Gaynor's "I Will Survive."

Clubs

Learn more about the iconic disco clubs of the 70s like Studio 54 and Paradise Garage.

What is Disco?

The term “disco” is derived from “discotheque,” a type of dance club that played recorded popular music. As both a musical genre and a cultural movement, disco reached peak popularity during the 1970s, shaping the decade’s association with personal freedom, vibrant social scenes, distinctive fashion, and rhythmic dance music. The genre is characterized by its use of synthesizers, electric instruments, energetic tempos, and the signature “four-on-the-floor” drumbeat, pioneered by drummer Earl Young.

The Rise of Disco

In New York City during the early 1970s, economic instability significantly impacted many neighborhoods, particularly those predominantly inhabited by communities of color. While the downturn affected the city as a whole, these areas experienced disproportionate hardship, contributing to a growing sense of social and cultural tension.

In 1970, disc jockey David Mancuso organized a private Valentine’s Day party at his loft in downtown Manhattan with the intention of covering his rent expenses. This event, however, would later be recognized as a pivotal moment in the development of a new cultural and musical movement.

The venue, which became known as The Loft, evolved into an inclusive social space that welcomed individuals from various backgrounds and supported emerging liberation movements. Although it operated outside of some legal frameworks, it fostered a sense of community and freedom. The music played at The Loft initially focused on danceable R&B. As similar venues began to emerge throughout New York City, disc jockeys began curating music that appealed to increasingly diverse audiences, contributing to the creation of a distinct musical style.

In 1973, journalist Vince Aletti wrote an article in Rolling Stone that documented this growing underground scene. He noted the strong presence of dance communities composed largely of Black, Latinx, and LGBTQ+ individuals. Around this time, the word “discotheque” began to be abbreviated to “disco,” marking the formal naming of a cultural phenomenon that would have a lasting influence on music and nightlife.

The War On Disco

During this period, individuals in the LGBTQ+ community faced systemic oppression from both legal institutions and broader society, including discrimination from law enforcement, colleagues, neighbors, and even friends. Laws at the time prohibited same-sex dancing and public displays of same-sex relationships. Although a 1971 legal change permitted same-sex dancing in New York City, societal attitudes remained largely intolerant. In response, many within the LGBTQ+ community focused on mutual support and solidarity, with disco emerging as a significant cultural outlet for this expression.

While mainstream venues continued to dominate popular nightlife, disco clubs, bars, and parties primarily existed in underground spaces that operated beyond legal and social norms. These environments provided LGBTQ+ individuals with a rare opportunity to express themselves freely and authentically, ultimately shaping the broader identity of the disco genre.

Disco served not only as a unifying social activity through dance but also as a creative outlet for musical innovation. Many of its key contributors were artists who had previously worked within other genres. During the 1970s, mainstream music charts were largely segregated, limiting opportunities for Black performers to achieve widespread success alongside acts such as The Beatles. As a result, artists who sought greater artistic freedom and visibility often turned to disco, where they could experiment beyond the constraints typically imposed on R&B performers in the mainstream industry.

By the late 1970s, disco had undergone significant transformation, shifting away from its original roots. The release of Saturday Night Fever in 1977 played a key role in popularizing the genre on a mainstream level. However, the film prominently featured the Bee Gees—artists not originally associated with disco—rather than highlighting performers from within the genre’s foundational communities. Around the same time, artists such as The Rolling Stones and Rod Stewart incorporated disco elements into their music. This trend marked a broader shift in control over the genre, as record labels, radio stations, and music charts that had previously marginalized disco began to dominate its direction. The result was a saturation of commercialized disco tracks that, according to many fans, lacked the genre’s original soul and cultural significance.

Longtime disco supporters expressed frustration over what they viewed as the co-opting and dilution of a movement that had deep personal and cultural meaning. They criticized mainstream media for promoting novelty hits like “Disco Duck,” which they felt trivialized the genre. Conversely, segments of mainstream culture blamed disco for pushing other musical styles, particularly rock, out of the spotlight. These competing perspectives fueled tensions among different listener groups. While artists faced increasing challenges within this changing landscape, the commercial sector—especially record labels—continued to benefit financially from disco’s popularity.

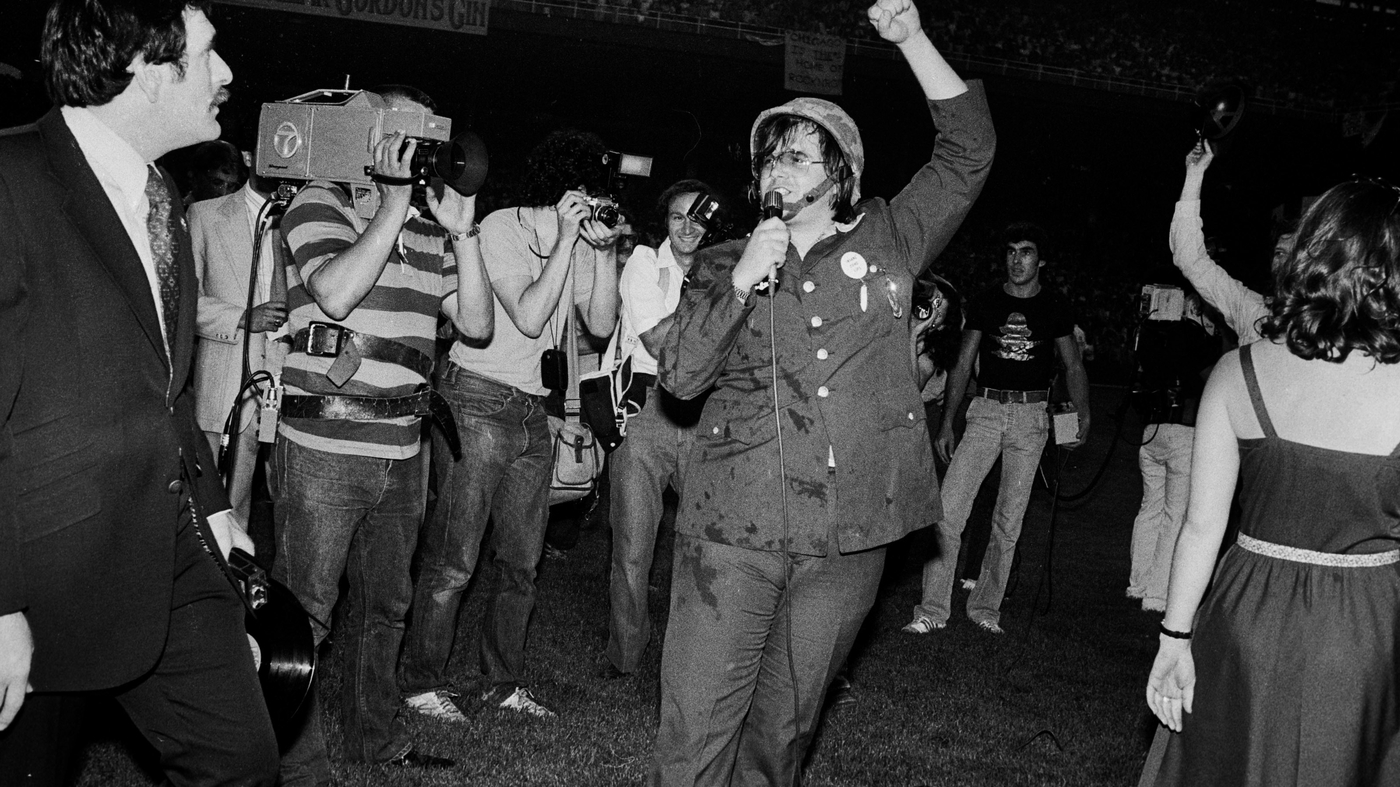

Disco Demolition

Disco often faced criticism for its openly sexual themes, expressive performances, and the atmosphere of its venues. These aspects drew disapproval from religious groups and other conservative segments of society. Because the genre was closely associated with LGBTQ+ communities and their expressions of identity and freedom—both of which were frequently targeted—opposition to disco frequently overlapped with anti-LGBTQ+ sentiment.

These tensions reached a climax on July 12, 1979, during an event known as "Disco Demolition Night" at Comiskey Park in Chicago. The event, led by radio DJ Steve Dahl—who had been dismissed after his station adopted an all-disco format—involved attendees destroying disco records on the field. While some participants framed the protest as a reaction to musical preferences, many artists and observers viewed it as an expression of deeper racial and homophobic bias. The backlash against disco coincided with the early years of the AIDS epidemic, and many saw this period as the effective end of disco’s mainstream prominence, as cultural and industry forces moved to marginalize the genre and its communities