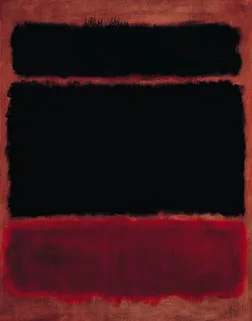

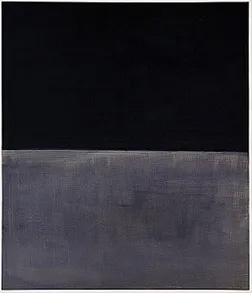

Rothko largely abandoned conventional titles in 1947, sometimes resorting to numbers or colors in order to distinguish one work from another. The artist also now resisted explaining the meaning of his work. "Silence is so accurate," he said, fearing that words would only paralyze the viewer's mind and imagination. By 1950, Rothko had reduced the number of floating rectangles to two, three, or four and aligned them vertically against a colored ground, arriving at his signature style. From that time on he would work almost invariably within this format, suggesting in numerous variations of color and tone an astonishing range of atmospheres and moods. In these paintings, color and structure are inseparable: the forms themselves consist of color alone, and their translucency establishes a layered depth that complements and vastly enriches the vertical architecture of the composition. Variations in saturation and tone as well as hue evoke an elusive yet almost palpable realm of shallow space. Color, structure, and space combine to create a unique presence. In this respect, Rothko stated that the large scale of these canvases was intended to contain or envelop the viewer—not to be "grandiose," but "intimate and human."

Mark Rothko.jpg)

Mark Rothko.jpg)

Mark Rothko.jpg)

Mark Rothko.jpg)