POP ART UNLEASHED: Bold Colors, Big Ideas

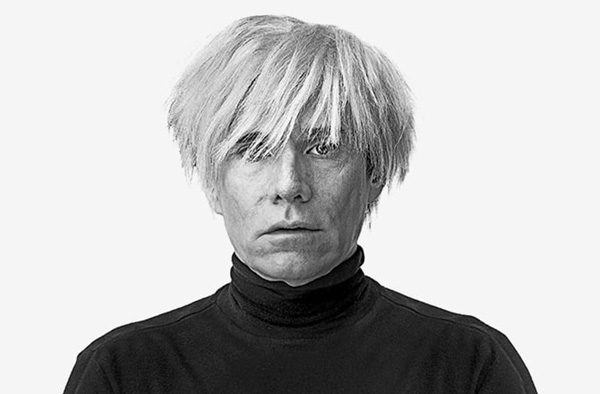

ANDY WARHOL

ANDY WARHOL Andy Warhol: The Icon of Pop Art

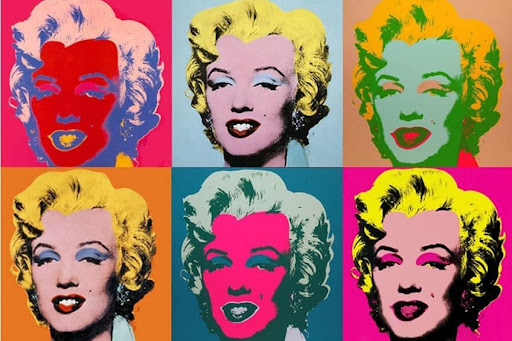

Marilyn Diptych (1962)

Silkscreen print and acrylic paint on canvas

Andy Warhol’s Marilyn Diptych is one of the most iconic works of the Pop Art movement, reflecting the intersection of celebrity, consumerism, and mass media. Created shortly after Marilyn Monroe’s death, the piece features 50 repeated images of the actress, with the left side in vibrant, artificial colors and the right side fading into black and white, symbolizing the fleeting nature of fame and mortality.

Using silkscreen printing, a commercial technique, Warhol highlights the mass production of celebrity culture, where individuals become brands and their images are endlessly reproduced. The imperfections and misalignments in the prints further emphasize how media distorts and commodifies public figures.

This artwork challenges traditional portraiture by presenting Monroe not as an individual but as a cultural icon, raising questions about identity, media influence, and the superficiality of stardom. Marilyn Diptych remains a powerful commentary on fame and society, making it one of the defining pieces of 20th-century art.

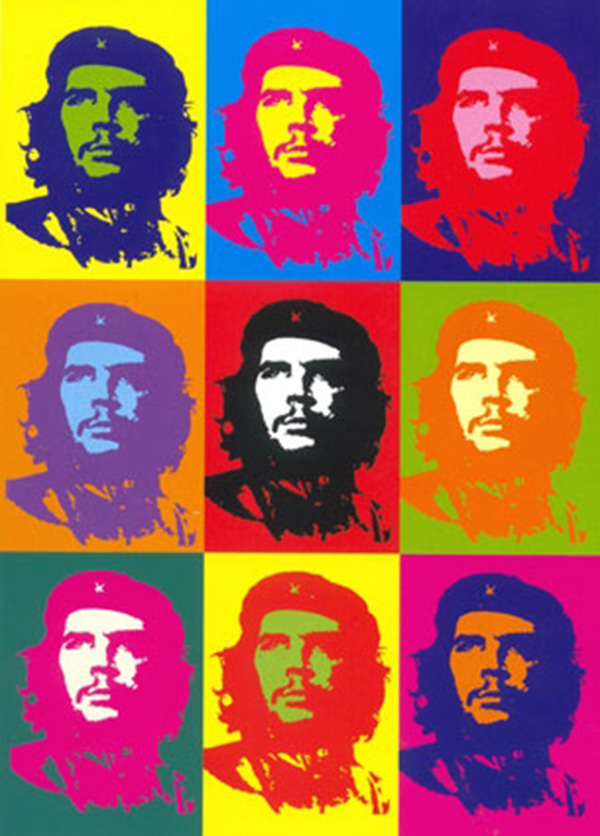

Che Guevara Pop Art (1968)

Silkscreen ink and acrylic on canvas

This artwork is a Pop Art reinterpretation of Alberto Korda’s famous 1960 photograph of Che Guevara, an image that has become one of the most widely reproduced symbols of revolution and political activism. Rendered in a grid of vibrant, contrasting colors, the work mirrors Andy Warhol’s silkscreen portrait style, emphasizing themes of mass production, iconography, and cultural symbolism.

By presenting Guevara’s face in bright, artificial tones, this piece strips away historical context and transforms him into a universalized pop culture icon, much like Warhol’s depictions of Marilyn Monroe and Mao Zedong. The repetition of the image reflects how media and propaganda turn historical figures into commercialized, widely recognized symbols, often divorced from their original ideological meanings.

This work invites viewers to question the intersection of politics, media, and consumerism, exploring how revolutionaries, like celebrities, can be commodified in contemporary culture.

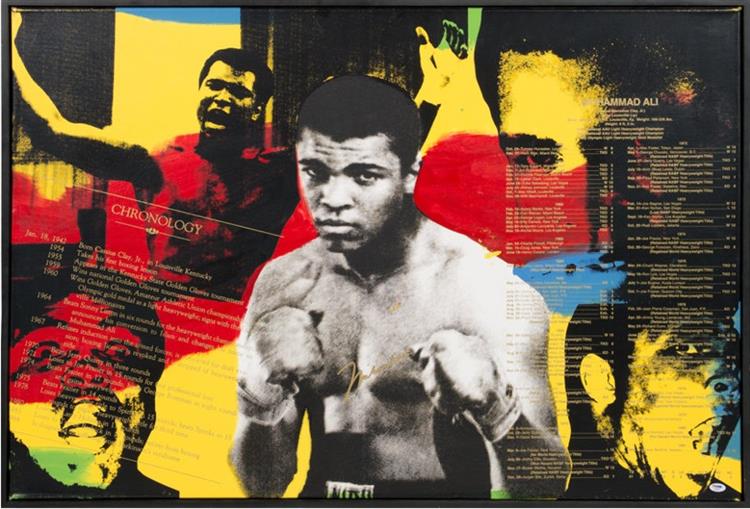

The Greatest (Series)

Silkscreen ink and acrylic on canvas

Andy Warhol’s The Greatest series is a striking tribute to Muhammad Ali, capturing the legendary boxer through bold colors, layered imagery, and screen-printing techniques. Warhol, known for elevating cultural icons to the realm of fine art, presents Ali not only as an athlete but as a larger-than-life figure in American history.

The composition features multiple overlapping portraits of Ali in action, emphasizing his power, confidence, and charisma. The combination of black-and-white photography with vibrant yellow, red, green, and blue accents adds dynamism, mirroring the energy of Ali’s boxing career. Additionally, elements of text—including a chronology of Ali’s achievements—are incorporated, reinforcing his status as a historical and cultural icon.

Through The Greatest, Warhol immortalizes Ali in the same way he did with celebrities like Marilyn Monroe and Elvis Presley, highlighting the boxer’s impact not just in sports but in civil rights, activism, and global culture. This work remains a testament to the power of image-making in shaping public perception and legacy.

Roy Lictenstein

Roy Lictenstein

Drowning Girl (1963)

Oil and synthetic polymer paint on canvas

Roy Lichtenstein’s Drowning Girl (1963) is one of the most iconic works of the Pop Art movement, showcasing his signature comic book-inspired style. Using bold black outlines, Ben-Day dots, and vibrant primary colors, Lichtenstein transforms a dramatic romance comic panel into a satirical yet visually striking fine art piece.

The image depicts a woman engulfed by stylized waves, her face frozen in melodramatic despair as she declares, "I don’t care! I’d rather sink—than call Brad for help!" This exaggerated emotional scene highlights themes of love, tragedy, and female independence, while also critiquing the over-the-top sentimentality of mass-produced romance comics from the 1950s and 1960s.

By isolating and enlarging this panel from its original comic book source, Lichtenstein elevates popular culture to high art, questioning the distinctions between mass media and fine art. Drowning Girl remains a landmark piece in contemporary art, symbolizing both Pop Art’s playful irreverence and its deep engagement with consumer culture and mass communication.

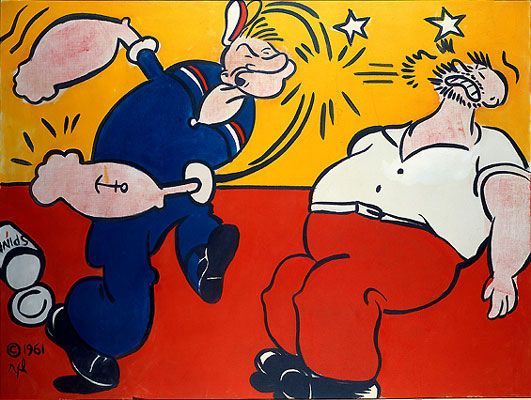

Popeye (1961)

Oil on canvas

Roy Lichtenstein’s Popeye (1961) marks one of his early explorations into Pop Art, drawing inspiration from comic book imagery and American popular culture. The painting features the classic cartoon character Popeye, mid-punch, knocking out his rival Bluto in a dramatic, exaggerated motion. The bold black outlines, flat primary colors, and simplified forms reflect Lichtenstein’s signature comic book style, which he would continue to refine in later works.

By appropriating mass-produced imagery, Lichtenstein challenges traditional notions of high and low art, elevating cartoons into the realm of fine art. The composition captures the dynamic energy and humor of classic American comics, while also commenting on themes of heroism, masculinity, and mass media representation.

Created at a time when Abstract Expressionism still dominated the art world, Popeye stands as a bold rejection of self-serious, gestural painting, embracing popular entertainment as a legitimate subject for modern art. This work played a pivotal role in shaping the Pop Art movement, celebrating the power of everyday imagery in contemporary culture.

Keith Haring

Keith Haring

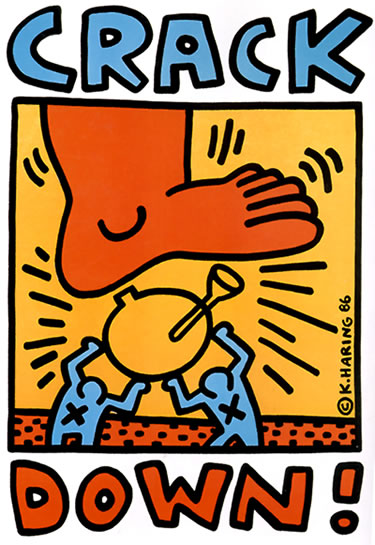

Crack Down! (1986)

Screenprint on paper

Keith Haring’s Crack Down! (1986) is a powerful example of his bold, graphic style and socially engaged activism. Created during the height of the 1980s crack cocaine epidemic, this work was part of Haring’s efforts to raise awareness about the dangers of drug abuse and the need for strong intervention.

The image features two blue figures holding a crack pipe, with a massive red foot stomping down, symbolizing law enforcement or societal action against drug use. The bright yellow, orange, and red palette adds to the urgency of the message, while Haring’s signature thick black outlines and dynamic movement make the piece instantly recognizable.

As an artist committed to public art and social causes, Haring used his platform to address drug addiction, AIDS awareness, and political injustice, ensuring that his work was accessible to all. Crack Down! remains a significant cultural artifact, reflecting both the crisis of the 1980s and the power of art as a tool for activism and education.

Best Buddies (1990)

Silkscreen print on paper

Keith Haring’s Best Buddies (1990) is a vibrant and joyful representation of friendship, unity, and human connection. Using his signature bold black outlines, simplified human figures, and bright primary colors, Haring conveys a universal message of inclusivity and support. The two figures, one yellow and one red, stand with arms around each other, symbolizing companionship and solidarity, while the radiating lines above them suggest energy, excitement, and positivity.

Haring’s work was deeply influenced by street art, activism, and social causes, and Best Buddies aligns with his mission of spreading love, equality, and accessibility through art. This piece was later associated with the Best Buddies organization, which supports individuals with intellectual and developmental disabilities.

As one of Haring’s final works before his passing in 1990, Best Buddies remains a powerful symbol of friendship and community, embodying his lifelong belief that art has the power to bring people together across all boundaries.

Takashi Murakami

Takashi Murakami

Flowers (2002)

Offset lithograph on paper

Takashi Murakami’s Flowers (2002) is a vibrant and playful example of his Superflat aesthetic, blending elements of Japanese pop culture, traditional art, and contemporary commercialism. The piece features a field of cheerful, multicolored smiling flowers, a recurring motif in Murakami’s work, symbolizing happiness, innocence, and mass-produced beauty.

With its bold outlines, flat colors, and cartoon-like precision, Flowers reflects Murakami’s fusion of anime, manga, and commercial design, questioning the boundaries between fine art and popular culture. The exaggerated expressions of the flowers evoke both genuine joy and artificial perfection, hinting at themes of consumerism and manufactured happiness in modern society.

Murakami’s Superflat movement, influenced by post-war Japanese visual culture, challenges traditional depth and perspective in art, embracing a bright, polished, and mass-reproducible aesthetic. Flowers remains an iconic work, celebrated for its whimsical yet thought-provoking approach to contemporary art and visual culture.

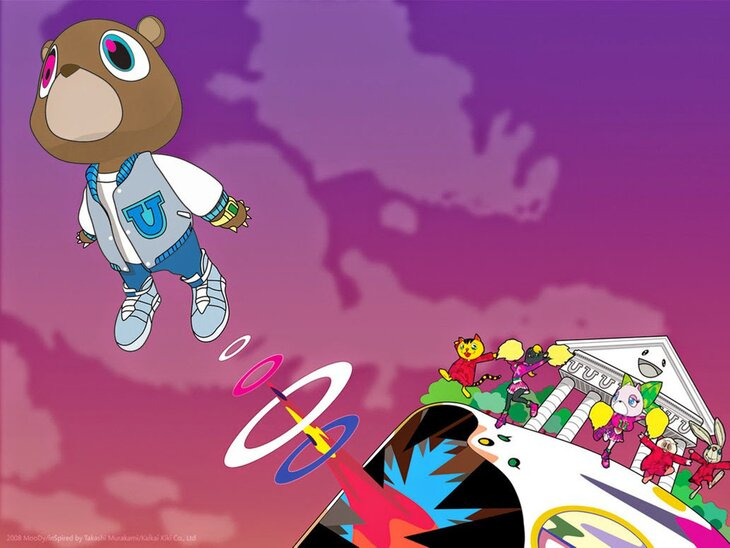

Gradudation (2008)

Digital illustration, printed artwork

Takashi Murakami’s Graduation (2008) is a striking example of his Superflat aesthetic, merging Japanese anime influences, pop culture, and contemporary music imagery. This artwork was created for Kanye West’s 2007 album Graduation, marking a significant collaboration between fine art and hip-hop culture.

The central figure, West’s mascot “Dropout Bear”, is depicted soaring into the sky against a vibrant, surreal landscape. The composition is filled with bold colors, sharp outlines, and a flat perspective, reflecting Murakami’s signature style that blends commercial aesthetics with high art. The cartoonish yet futuristic imagery suggests themes of aspiration, transformation, and artistic evolution, aligning with the album’s themes of personal and creative growth.

Murakami’s Graduation challenges traditional boundaries between music, fashion, and contemporary art, demonstrating how visual storytelling can enhance cultural narratives. This piece remains a landmark in modern art, symbolizing the fusion of global pop culture, digital aesthetics, and artistic innovation.

Yayoi Kusama

Yayoi Kusama

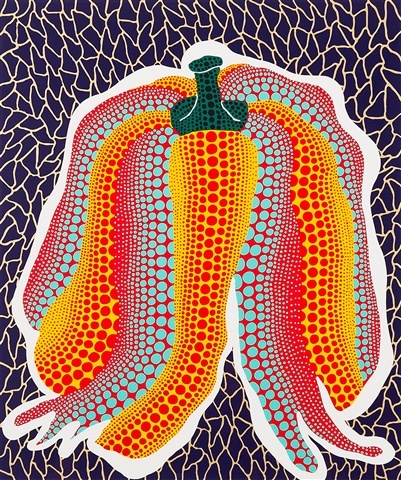

Pumpkin (1990)

Acrylic on canvas

Yayoi Kusama’s Pumpkin (1990) is a vibrant and mesmerizing example of her signature obsession with repetition, pattern, and organic forms. This work features a stylized pumpkin composed of intricate polka dot patterns, a recurring motif in Kusama’s artistic practice. The bold contrasts of red, yellow, and turquoise dots against a dark background create a sense of movement and visual depth, embodying her concept of infinity and self-obliteration.

For Kusama, the pumpkin is a symbol of comfort, strength, and personal nostalgia, reflecting memories of her childhood in rural Japan. Her repetitive dot patterns—an extension of her lifelong hallucinations—serve as a meditative and immersive exploration of identity, nature, and the cosmos.

Kusama’s work challenges traditional boundaries between fine art, design, and conceptualism, and Pumpkin stands as a testament to her ability to transform simple organic subjects into powerful expressions of infinity and interconnectedness. This piece is part of a larger body of work that has made Kusama one of the most celebrated contemporary artists of our time.

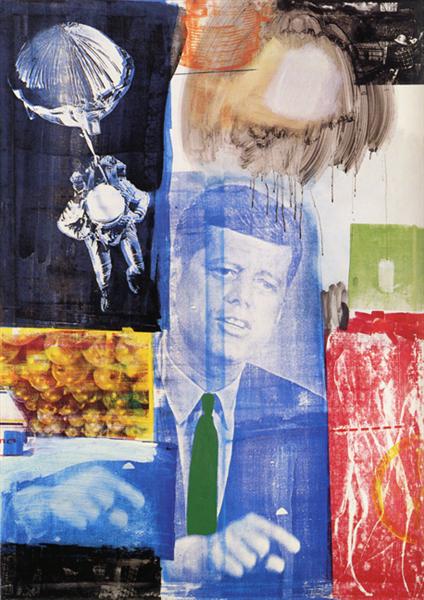

"Retroactive I" (1964) by Robert Rauschenberg

Robert Rauschenberg’s Retroactive I (1964) is a striking example of Pop Art and Neo-Dada, blending silkscreen printing, collage, and gestural painting to capture the dynamic, media-driven world of the 1960s. The artwork presents a fragmented composition of John F. Kennedy, an astronaut, a nuclear explosion, and consumer imagery, reflecting themes of politics, technology, and mass communication.

Created shortly after Kennedy’s assassination, the blue-tinted image of the former president conveys both a sense of leadership and a memorial quality, while the surrounding elements, including an astronaut in free fall and a blurred atomic blast, highlight the scientific progress and Cold War anxieties of the era. The juxtaposition of mass media images and expressive brushstrokes blurs the line between fine art and commercial reproduction, challenging traditional artistic boundaries.

Retroactive I serves as both a tribute and a critique of contemporary American culture, emphasizing how rapidly images and information shape public perception. Rauschenberg’s innovative approach influenced future generations of artists, making this piece a defining work in the evolution of modern art.